And it is a shame. Because the truth about modern, well-designed murder mysteries is far more relaxed and far more human than most people expect.

This post is for the parents, hosts, teachers, friends, and planners who love the idea of a mystery game but hesitate because they are picturing awkward accents, forced improv, or a room full of people staring at one another waiting for someone to perform. That version exists. It just is not the kind we make.

The short answer? No, you do not need to be a good actor. Not even close.

Where the Acting Fear Comes From

Most people’s mental image of a murder mystery comes from one of three places.

First, movies and TV. Everyone is dramatic. Everyone is in costume. Someone is monologuing. It looks fun on screen but exhausting in real life.

Second, that one friend who went all-in. You know the one. Accent, props, character voice, the whole thing. Impressive, yes. Also intimidating.

Third, old-school mystery kits. The kind that drop a vague character paragraph on you and then say “improvise” like that is a small ask. For some people, it is. For most people, it is not.

If you are hosting a group with kids, teens, shy adults, grandparents, or a mix of all of the above, you cannot assume everyone is comfortable performing. And you should not have to.

What Acting Actually Looks Like in a Good Mystery Game

In a well-structured mystery, acting is optional seasoning. Not the main dish.

At its core, playing a murder mystery is about reading, listening, asking questions, and making connections. It is closer to a guided group puzzle than a play. The “acting” part is usually nothing more than reading a short introduction and then following prompts during the game.

That distinction matters.

Reading is not acting. Talking in your normal voice is not acting. Saying what the card tells you to say is not acting. It is participation.

The moment a game relies entirely on improvisation is the moment half the room starts checking out.

Scripts Are Not the Enemy

Some people hear “scripted” and think boring or stiff. In reality, scripts are what make mystery games accessible.

A good script does three important things:

It breaks the ice. Everyone starts on equal footing, reading something out loud. No one has to invent an opening line.

It sets expectations. Players immediately understand the tone, the world, and how serious or silly the game is supposed to be.

It gives permission. Permission to read plainly. Permission to not do a voice. Permission to relax.

In our games, the introduction is intentionally specific. You are told exactly what to read. You can stand up and read it word for word in your own voice and you are doing it right.

Some people will naturally add flair. Others will not. Both are fine. The group energy balances itself out surprisingly fast.

Prompts Beat Improvisation Every Time

After the introduction, most of the game unfolds through guided objectives.

This is where a lot of mystery games either shine or fall apart.

Instead of saying “go act suspicious,” a strong game gives concrete prompts. Things like:

Correct people’s grammar when they speak to you because you are a linguist.

Casually mention your expensive hobbies and wardrobe because you are wealthy.

Defend your decisions whenever someone questions your role.

These are not lines you must memorize. They are behavioral nudges. They tell you how to move through conversations without forcing you to invent dialogue.

You are never standing there thinking, “What am I supposed to do right now?” You always have a default action.

And when people know what to do, they relax.

The Power of the Fallback Instruction

One of the most underrated features in any group game is a fallback.

A clear instruction that says, “If you are unsure, do this.”

That single line removes pressure instantly.

It gives quieter players a way to stay involved without chasing conversations. It gives kids something concrete. It gives nervous adults a job instead of an expectation.

We have seen kids who hate pretend play light up because their role had a specific physical action. Standing guard. Delivering items. Observing quietly. Being present without performing.

Oour son played a palace guard in The Mystery at the Desert Palace and spent a decent chunk of time standing by a doorway because the card told him to, after he finished his objectives. He felt confident. He felt useful. He felt in character without having to speak much at all.

That is not accidental design. That is intentional inclusion.

If This Is You, You Are Not the Problem

If you are thinking, “I would rather narrate than act,” or “I am fine talking, just not pretending,” or “I shut down when I feel put on the spot,” you are not difficult.

You are normal.

Most people do not want to perform. They want to participate.

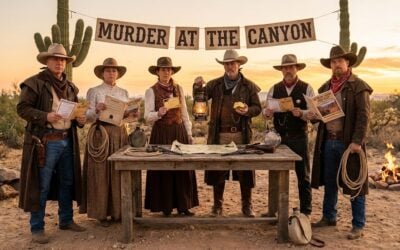

Our games are written in such a way that merely with a tiny amount of costume effort (like just a Cowboy hat), plus following the prompts, you’ll fit right in and still feel comfortable.

The goal of a good mystery game is not to turn your guests into actors. It is to give them a shared experience where everyone feels comfortable contributing in their own way.

A Quick Way to Test This Without Risk

If you are still unsure whether a mystery game will work for your group, there is a low-stakes way to find out.

About fifteen percent into planning most parties, hosts start second-guessing everything. Will people like this? Will it be awkward? Will my quiet friend hate it?

This is exactly why we offer a short, light mini mystery that you can try with just a few people. It takes about fifteen minutes. It is designed to be playful, low pressure, and approachable. No murder. No heavy roles. Just conversation and laughs.

Think of it as a test drive, not a commitment.

Click HereWhy This Matters for Mixed Groups

Many mystery games quietly assume everyone is the same age and temperament. Real groups are not like that.

You might have an eleven-year-old, a teenager, an introverted adult, and someone who loves the spotlight all in the same room. If the game only works when everyone performs at the same level, it is going to fail.

Guided prompts, scripts, and fallback instructions allow each person to engage at their comfort level. The spotlight naturally shifts around the room. No one is forced to carry the energy alone.

Ironically, this structure often leads to more creativity, not less. When people feel safe, they experiment. When they feel pressured, they retreat.

What You Should Look for Before Buying a Mystery Game

If acting anxiety is on your radar, scan the product description carefully.

Look for language about scripts, prompts, guided rounds, or structured objectives. Be wary of vague phrases that promise “total freedom” or “full improvisation” without support.

Ask yourself a simple question. Could someone participate fully by reading and following instructions alone?

If the answer is yes, you are in good shape.

You Do Not Need a Broadway Cast

A successful mystery night is not measured by accents, costumes, or dramatic flair. It is measured by laughter, conversation, and that moment near the end when everyone suddenly starts connecting dots.

That moment does not require acting talent. It requires clarity.

When the game tells people what to do and gives them permission to be themselves, everything else falls into place.

If you have been holding back from hosting or buying a mystery because you are worried about the acting piece, consider this your green light. You do not need performers. You need people who are willing to read a card, talk to each other, and have a little fun.

And that is a much lower bar.

Still Curious?

If you want to see how this style of mystery feels before committing to a full game, start small. Play something quick. Watch how your group reacts. Notice who relaxes once the pressure is gone.

Then decide if it’s a good fit for you.

Click Here

0 Comments